Cryptonarratives: Part 3, Dreams and Sacrifices

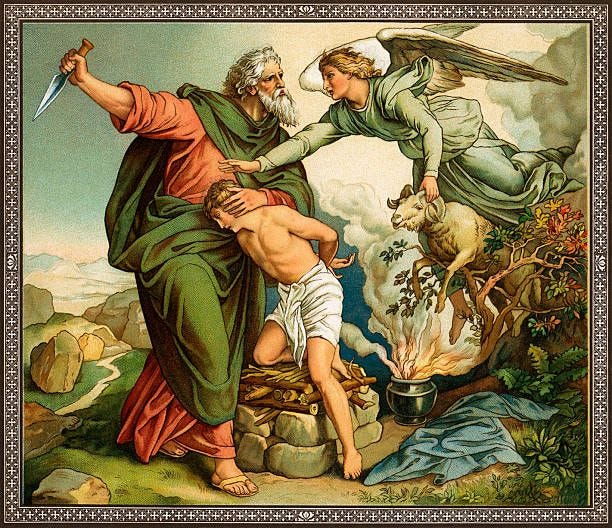

The Cryptonarrative in the story of Abraham and Isaac.

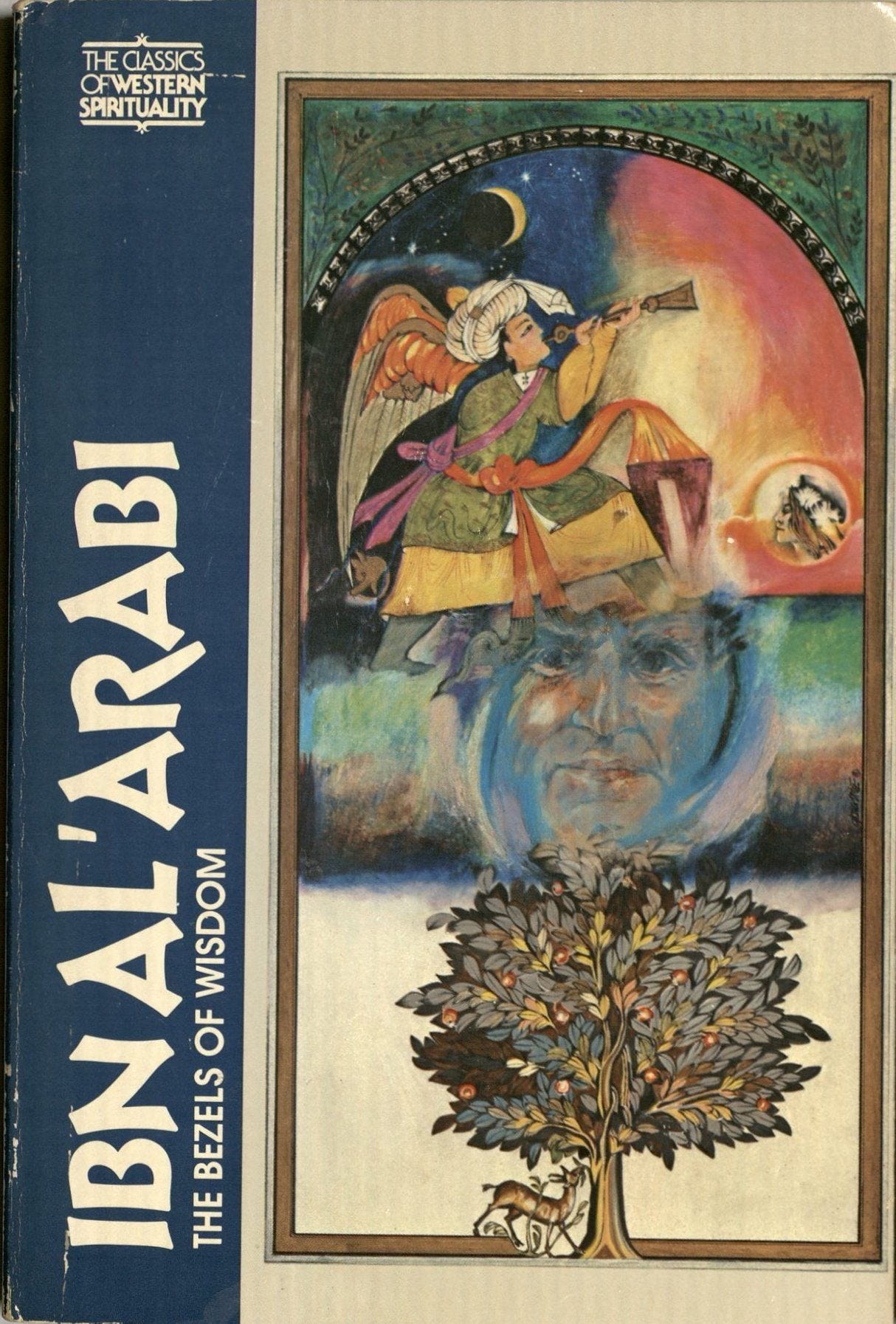

There’s a fascinating cryptonarrative in Fusus Al Hikma on the topic of Abraham’s Sacrifice. It’s covered in the following chapters: The Bezel of Wisdom of Ibrahim, al-ḥikma al-qalbiyya fī kalimati Ibrāhīmiyya (The wisdom of the heart in the Abrahamic words). and the subsequent chapter: The Wisdom of the Heart in the words of Isaac.

The Signs and Symbology of Dreams

Ibn Al Arabi recounts the origin of Abraham’s decision to sacrifice his son. Abraham dreamed that he was told to sacrifice a ram (or goat), and he saw in the dream “A goat in the form of his son Isaac”. Now, if you speak some Arabic, you’ll know that the words we have for form and appearance are often the same. Bi-Shakl can mean ‘of the form of’ or ‘it looks like’ so you can read the Arabic as “a goat that looked like his son Isaac”.

In Arabic, when someone says bil shalk da, we only know by context whether it means ‘in the form of’ or ‘it looks like’. Form or shape, and appearance, are two completely different things. Context is important in this case. A goat can’t take the form of your son, I imagine, but its face can look a bit human in some way, especially in dreams where the subconscious imagination has free rein.

In other words, the goat in the dream had a humanish face that looked like Isaac, and Abraham believed that the goat represented sacrificing his son. It turns out (from Ibn Al Arabi’s expositions on Abraham and Isaac) that Abraham interpreted the dream incorrectly. Since he wasn’t versed in the symbolic language of dreams, he took the dream somewhat literally.

In the dream, the goat with Isaac’s face was symbolic. It was not meant to signify that Abraham should slaughter Isaac. God intended Abraham to sacrifice a goat or ram, and doing so was meant to symbolize a huge sacrifice, just as great as sacrificing a son. Abraham was never meant to actually sacrifice Isaac. God never intended Abraham to commit filicide. But the dream made Abraham believe that God wanted him to sacrifice his son.

For me, the cryptonarrative uncovered by Ibn Al Arabi’s wisdom is that we don’t fully understand the human mind, or dreams. We are all prone to making assumptions about what dreams, and what the signs and symbols of the subconscious imply. We are given to assuming the worst, and we have a tendency towards morbidity, assuming that death is the ultimate sacrifice.

Dreams mislead us if we don’t know how to interpret them. By extension, our own minds mislead us if we don’t fully understand them. As a spiritual communique, dreams have their own language. Because Abraham’s schema wasn’t sophisticated enough to understand the goat with Isaac’s face, he misread the dream and almost sacrificed his son.

Sufi mystics have studied and cataloged a hidden psychological language in their books on dreams and the language of the subconscious, and they’ve used that language to encode their poetry with secrets about the divine.

Reading through conversations about dreams and spiritual acts reminds me of reading the books of Carlos Castaneda. I’m reminded that all the prophets, Abraham, Isaac, and the prophet Mohammed, were mystics who communed with God through dreams and meditation, and that’s not so different from some of the shaman and naguals in north america, whom you read about in Castaneda’s accounts.

Goodbye Human Sacrifices!

There are plenty of discussions in these two chapters of the Fusus Al Hikma about the power of God to amplify the esoteric impact of a simple act of sacrifice, making the sacrifice of a goat akin to sacrificing a son, if done in the name of God. For the author, that is what the dream was trying to show Abraham. In this regard, Ibn al Arabi is trying to emphasize that there’s no need to continue the practice of human sacrifice to the gods, or to God.

The story of the Abrahamic sacrifice is all the more important when we come to understand that many Western civilizations used to practice ritual human sacrifice. There’s a history of Ancient Greeks and plenty of other proto-Western cultures, sacrificing men and women to their gods. We never think of the ancient Greeks as beings so primitive, but in plenty of cases they were superstitious, conservative, and barbaric, (wait until you find out how they treated their wives).

The Abrahamic event, with the intervention of Gabriel, marks the end of human sacrifice in the Western world, replacing it with animal sacrifices to appease God. People in the Middle East would slaughter animals for food anyway, so what’s the harm in applying religious significance to it? If anything, it makes the feasting on meat more periodic instead of constant. Since uncontrolled grazing and cattle farming likely created the largest desert the planet has ever known (the Sahara), it might not have been a bad thing to limit animal consumption to a few times a year, especially in the ancient world.

The main narrative on the Abrahamic event ought to be that God doesn’t want us to sacrifice other human beings in his name. God has had enough of human sacrifice and would rather we sacrifice cattle.

And the cryptonarrative would be that dreams and spiritual messages are best brought to mystics who are literate in the language of the subconscious.

Both Abraham and Narkissos’s stories have people drawing incorrect conclusions from the evidence they have available to them, and their way of understanding it.

The next story also involves a father and son, but whereas the prior has a father who misunderstood a message, the second has a son who is assumed to have ignored his father’s advice.

Now that you know how cryptonarratives work, I’m going to give you a new one for Icarus. This one’s mine!